If illegal wildlife trade and their habitate destruction are not stopped, deadly virus like Corna, Zika, Nipa can be infected to human in northeastern Indian region. Chandan Kumar Duarah, the science editor of Asomiya Pratidin has warned. The outbreak of diseases like corona virus, hurbouring by wildlife can be spread to human. it has already been confirmed that the corona virusvirus came from wildlife through a Wuhn market of wildlife parts and flesh.

Wildlife poaching and killing taking place in Northeast India and animals and parts have been supplied to Chinese markets for decades. These illegal activities accelerated forest and biodiversity destruction in Assam as well as in the Northeastern Indian region. Habitat loss and wildlife killing has been rampant in Northeastern India, mostly in Assam. Timber logging, road building, tea cultivation expansion, rubber plantation and encroachment are responsible for haitate loss in the region, Duarah said.

If these unlimited activities can’t be stopped, many wildlife will come near human habitat and eventually deadly virus will transmit to human and different animals. There are so many Pangolin and thousands of different species of bats in states of Northeastern India including Assam and many of them were caught and killed illegally to meet the demand of of Chinese mmedicinal demand. It is estimated that around 30,000 pangolins were caught or killed in Northeast India to meet the Chinese medicinal market demand.

Habitat destruction threatens vast numbers of wild species with extinction, including the medicinal plants and animals we’ve historically depended upon for our pharmacopeia. It also forces those wild species that hang on to cram into smaller fragments of remaining habitat, increasing the likelihood that they’ll come into repeated, intimate contact with the human settlements expanding into their newly fragmented habitats. It’s this kind of repeated, intimate contact that allows the microbes that live in their bodies to cross over into ours, transforming benign animal microbes into deadly human pathogens.

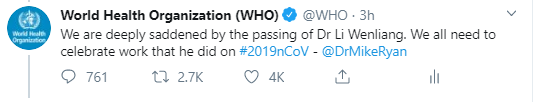

As China is battling the outbreak of coronavirus, many studies have been doing the rounds linking the virus with wild animals. Experts with the World Health Organization (WHO) say there’s a high likelihood the new coronavirus came from bats. The Corona virus has so far killed around 2200 people in China and sickening more than 84,000 — eight times the number sickened by SARS.

It is believed that a wildlife market in Wuhan in China could have been the starting point for the outbreak. First infected were those who worked in with sea food animals. So it was assumed to be the virus came from sea animals. A WWF study showed illegal wildlife trade is worth around $20bn per year. It is the fourth biggest illegal trade worldwide, after drugs.

Many in China want the temporary ban on wildlife to be permanent while Chinese leader Xi Jinping said the country should “resolutely outlaw and harshly crack down” on the illegal wildlife trade because of the public health risks it poses. Chinese officials reveal that about 1.5 million markets and online operators nationwide have been inspected since the outbreak of coronavirus and 3,700 have been shut down while around 16,000 breeding sites have been cordoned off.

Many studies revealed that bats host many kind of virus incuding corona. According to a 2017 study, Ebola outbreaks, which have been linked to several species of bats, are more likely to occur in places in Africa that have experienced rampant deforestation. Cutting down the trees bats’ used to forced them to roost in trees in backyards and farms instead, increasing the likelihood that a human might. If someone take a bite of a piece of fruit covered in bat saliva or hunt and slaughter a local bat, exposing herself to the microbes sheltering in the bat’s tissues. It happens by pangolin too. When human catch or touch pangolin flesh, the deadly virus transmit to human in a easy way.

The outbreak of the virus has prompted calls to permanently ban the sale of wildlife but the Chinese government has made it clear the ban would be temporary. Conservtionists and environmentalists had been appealing to stop wildlife markets in Cina, but the Chinese Government had turned a deaf ear. China has not yet pronounced any word of possibility of permanent ban despitecan the pandemic and death of more than two thousands valuable lives. Beijing announced a similar ban in the event of the outbreak of Sars in 2002. However, authorities relaxed the ban and the trade bounced back.

Offcourse the prime suspect is the bat. One now-debunked theory that made the rounds suggested, a snake. That’s not the fault of wild animals. But now the ‘culprit’ is the Pangolin. But people must know that wildlife has been harbouring many kinds of virus ( fatal and non-fatal) for thousands of years without harming to host animals and plants. These virus and microbes has been a crucial part of biodiversity as well as nature for thousands of years. In fact, most of these microbes live harmlessly in these animals’ bodies.

The virus’s animal origin is a critical mystery to solve. But speculation about which wild creature originally harbored the virus obscures a more fundamental source of our growing vulnerability to pandemics: the accelerating pace of habitat loss. Habitat destruction threatens large numbers of species with extinction, including the medicinal plants and animals humankind historically depended upon for our pharmacopeia. The problem is the way that cutting down forests and expanding human habitat and socalled development activities forced come out animal microbes to adapt to the human body.

The epidemiologist Larry Brilliant once said, “Outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional.” Sonia Shah is a science journalist and the author of “PANDEMIC: Tracking Contagion from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond” says- “But pandemics only remain optional if we have the will to disrupt our politics as readily as we disrupt nature and wildlife. In the end, there is no real mystery about the animal source of pandemics. It’s not some spiky scaled pangolin or furry flying bat. It’s populations of warm-blooded primates: The true animal source is us.” Government’s liberation of extractive industries and industrial development from environmental and other regulatory constraints can be expected to accelerate the habitat destruction that brings animal microbes into human bodies, she said.

Markets selling live animals are considered a potential source of diseases that are new to humans

Most of the samples taken from the Wuhan market that tested positive for the coronavirus, were from the area where wildlife booths were concentrated. It is said that more than 70% of emerging infections in humans are estimated to have come from animals, particularly wild animals. Rapid deforestation and rampant destruction of habitats bring wildlife into close proximity with human habitations. It is more likely there are chances of spread of deadly viruses as people come into closer contact with animals and their viruses. The viruses behind Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (Sars) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (Mers) are also thought to have originated in bats. Civet cats and camels respectively, are thought to be the carriers of these viruses before being transmitted to humans.

A large number of viruses in the animal world have the potential to spread to humans, warn experts. Dormant deadly viruses could be transmitted to humans through wildlife like bats, pangolins, geckos etc as these animals have been largely traded. Markets selling live animals are considered a potential source of diseases that are new to humans. The Sars virus was found to have come from civet cats sold in Chinese markets. Bushmeat in Africa is thought to be a source for Ebola. Since 1940, hundreds of microbial pathogens have either emerged or reemerged into new territory where they’ve never been seen before. They include HIV, Ebola in West Africa, Zika in the Americas, and a bevy of novel coronaviruses. The majority of them—60 percent—originate in the bodies of animals. Some come from pets and livestock. Most of them—more than two-thirds—originate in wildlife.

The wildlife products industry is a major part of the Chinese economy and has been blamed for driving several species to the brink of extinction. China’s demand for wildlife products, which find uses in traditional medicine, or as exotic foods, is driving a global trade in endangered species. “The Chinese market largely remains a threat to wildlife conservation, said Mubina Akhtar, a wildlife activist. “Rampant killing of wildlife continues in Northeast India and China remains the major consumer. From rhino horn to geckos, pangolins, skin-paws- bones of tiger and other wild cats have been regularly smuggled to the markets in South Asia. A permanent ban on the trade in wildlife by China would have been a vital step in the effort to end the illegal trading of wildlife,” she added.

Conservationists hope the outbreak could provide China with an opportunity to prove it is serious about protecting wildlife. China had earlier put a ban on the import of ivory – after years of international pressure to save elephants from extinction. However, an end to wildlife trade seems distant. Even if China regulates or bans it, wildlife trade is likely to continue in the poorer regions of the world where it continues to be an important food source.

According to Duarah, wildlife trade needs to be regulated globally both for conservation and protecting human health. While it allows for greater surveillance and testing for viruses in farm animals, in case of wildlife–regulation, improved monitoring and public education hold the key to better control the problem. Therefore countries need to contribute to exchange information as well as to improve food safety measures across a range of issues that also include pathogenic bacteria, viruses, and parasites.